Note to Reader: An analysis of the events and dates that appear in this timeline will be presented in the next post.

© 2017, Robin Slicker. All Rights Reserved.

Note to Reader: An analysis of the events and dates that appear in this timeline will be presented in the next post.

© 2017, Robin Slicker. All Rights Reserved.

Like her husband’s, Philip’s, life story, I didn’t want to tell Magdlena’s story as a list of events and dates. Boring! Lacking the colorful details of Magdlena’s personal life, I decided to place her story within the context of Germany’s history. It’s a simplified version, of course. Nonetheless, it will hopefully make Magdlena as a person seem more real and her story more interesting.

The reader should take note of the words that convey possibility. To make the narrative more meaningful, I have mixed unsubstantiated information – like her father’s possible occupations – with the facts of Magdlena’s life. I only hypothesized about our ancestors’ lives when there was enough information to support it. For example, in 19th century Germany, most people worked as a craftsmen or peasant.

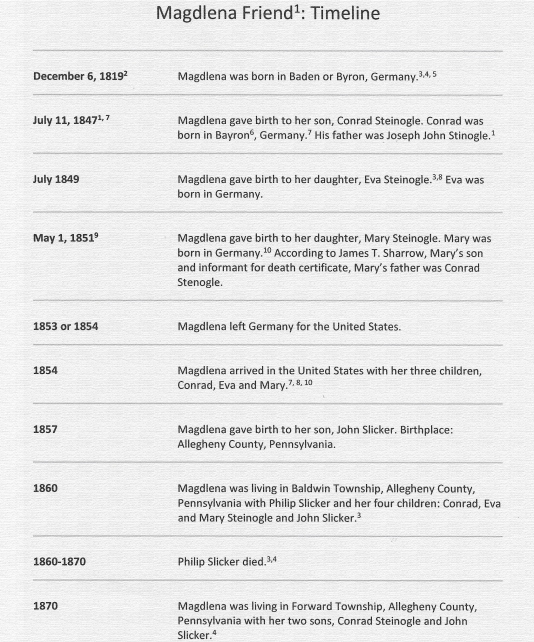

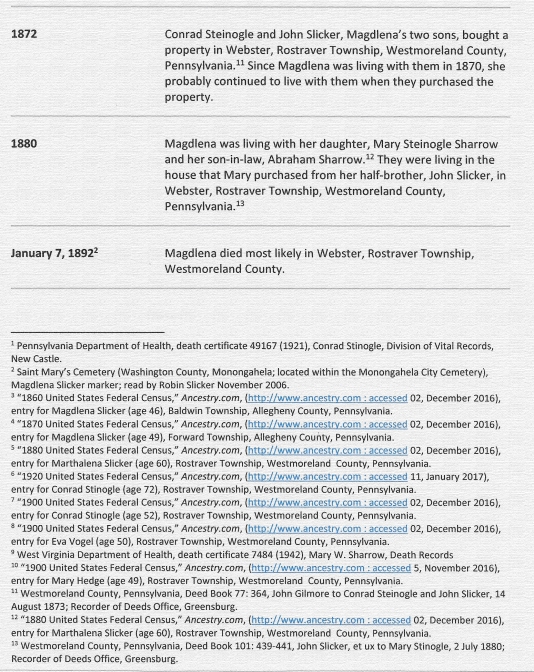

It was a cold December day in 1819[1] when Magdlena Friend was born in the Grand Duchy of Baden, an independent country in the southwest region of what is present-day Germany. Only four and half years had passed since Baden along with 38 other German-speaking states formed the German Confederation.

This was Magdlena’s Germany, a loosely organized confederation of sovereign states.

Magdlena’s home was nestled somewhere in the landscape of Baden. She along with her family most likely attended the Catholic Church. Her child-hood was an era marked by political and social unrest. Change was in the air as the middle class pushed to have more participation in government, a unified Germany, free markets, freedom of speech, press, and religion.

Magdlena’s parents’ economic-social status determined the family’s lifestyle. Her father most likely worked either as a craftsmen or a peasant. If he belonged to the peasant class, he may have worked for one of the wealthy landowners of rural Baden; or perhaps, he was one of the luckier peasants, who worked their own small plot of land.

On the other hand, Magdlena’s father may have worked as a craftsman. Craftsmen began as apprentice. Through training they advanced to journeymen and ultimately a few advanced to master. Although craftsmen were respected throughout their community, their living standard varied greatly. Whether he was a craftsmen or peasant, Magdlena’s father most likely worked long hours to provide economic support for the family.

During the nineteenth century young Germans who were not able to economically provide for a family would often wait until their late twenties to married. They would work and save money until they could afford to establish an independent family.

So, in July 1847, we find Magdlena at age twenty-six married to John Joseph Steinogle[2] and giving birth to her son Conrad. As she cared for her new-born, Magdlena must have wondered about the uncertainty of his future. Unemployment and political and social discontentment were on the rise. The mood throughout the German Confederation was very similar to the mood experienced throughout other countries in Europe.

Restlessness ignited on February 4th, 1848 in Paris and continued throughout the month. A result of this month-long political agitation was the overthrow of France’s King Louis Phillipe. As the fire of political revolution continued to stir in France, a spark landed in neighboring Baden. In a few unorganized instances, peasants living in the northern territory of Baden burned mansions of local aristocrats. From here the fire of revolution spread to other states in the German Confederation.

Despite the fact the Grand Duchy of Baden had the most liberal constitution among the states of the German Confederation, it became a hot bed of activity as the middle class formed convenient alliances with the working class. The alliance was a shaky one as the middle class consisting of well-educated students, intellectuals and businessmen demanded political reform and the working class sought radically improved working and living conditions.

Out of fear, the princes and rulers of the German Confederation gave in to many of the demands and began to carry out reforms. But recognition of freedom of religion and freedom of assembly among other basic reforms were not enough for many of the revolutionists. Many revolutionists of Baden further demanded a republican government while the rebels of other German states preferred to keep the hereditary monarchy.

Throughout 1848 and 1849. bloody battles were fought throughout Baden and other states of the German Confederation. Thousands of lives were lost. Many of the surviving rebels were forced into exile.

In May 1849, as the political turmoil continued, Magdlena was expecting another child. Her son, Conrad, was walking. Her husband, despite the civil unrest, no doubt ventured out every day to his place of employment – a living had to be earned. Leopold, the Grand Duke of Baden had fled the country. In his absence, the revolutionary forces formed a provisional government. They were moving close to obtaining the republican government they desired.

In June, the Federal Troops of the German Confederation accompanied by the Prussian Army Corps and a body of Hessian troops invaded Baden. Bloody skirmishes were fought throughout the month. The revolutionists who were never well-coordinated and had failed to agree on a common set of outcomes began to fall apart. The Federal Troops and Prussian Army captured and executed many of the rebels. In July as those rebels who were not captured exited Baden, Magdlena was welcoming her daughter, little Eva[3] into a world restored to peace.

In 1851 the third Steinogle child, Mary, was born[4]. Mary is a fascinating story. As if she were a magician, she performed a little hocus-pocus and mysteriously disappeared for a moment in time. But when she reappeared, she did not come alone. A rule-breaker – intentionally or unintentionally – and bathed in an aura of mystery, Mary is not your ordinary 19th century gal.

But now is not the time for Mary’s story. Her story must wait until another time… another post. For now, let’s get this family to their new home in Pennsylvania.

In the years after the 1848-1849 Revolution, German experienced its largest flux of emigration. It was at the tail end of this peak when Magdlena with her three children embarked on a journey to a new life in the United States.

Bibiography

Huber, Leslie Albrecht. Understanding Your Ancestors. http://www.understandingyourancestors.com accessed 5, November 2016

Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_Revolution accessed 5, November 2016

Wikipedia. German Revolutions of 1848-49. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_revolutions_of_1848–49 accessed 5, November 2016

Wikipedia. Grand Duchy of Baden. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden accessed 5, November 2016

Sources

[1] Saint Mary’s Cemetery (Washington County, Monongahela; located within the Monongahela City Cemetery), Magdlena Slicker marker; read by Robin Slicker November 2006.

[2] Pennsylvania Department of Health, death certificate 49167 (1921), Conrad Stinogle, Division of Vital Records, New Castle.

[3] “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 5, November 2016), entry for Eva Vogle (age 50), Rostraver Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

[4] “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 5, November 2016), entry for Mary Hedge (age 49), Rostraver Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

© Robin Slicker, 2016. All Rights Reserve.